Dear Friends,

Singapore Youth Olympic Games 2010

The Armenian Community in Singapore warmly embraced the Armenian National Olympic Team at the first-ever Youth Olympic Games, held in Singapore from August 14-26.

The community organised several events with the goal of having the Armenian Team experience the amazing wonders of Singapore. The Team visited a number of landmarks representing the positive Armenian historical contributions to Singapore, including: Armenian Street, the Raffles Hotel, the Straits Times (national newspaper), the Vanda Miss Joaquim (Singapore's national flower) and the Armenian Apostolic Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator, the oldest Christian Church in Singapore.

The events culminated in a reception held at the Armenian Church in Singapore where members of the local Armenian Community and the Armenian National Olympic Team were able to meet and share their impressions about their experience in Singapore.

18th Century Madras Armenians Envision an Independent Armenia

DREAMS COME TRUEby David Zenian

As the Seljuk conquest of Armenia in the 11th century and the loss of the last Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia in 1375 led to the creation of Diaspora communities worldwide, the bold efforts by a group of Armenians in the Indian city of Madras in 1772 was the first step in the long struggle for an independent Armenian state.

As the Seljuk conquest of Armenia in the 11th century and the loss of the last Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia in 1375 led to the creation of Diaspora communities worldwide, the bold efforts by a group of Armenians in the Indian city of Madras in 1772 was the first step in the long struggle for an independent Armenian state.

While living oceans away from America, where events like the Boston Tea Party and the American War of Independence were about to unfold, the Armenians of Madras were moving on a parallel track. Freedom and democracy were as much a dream for the Armenians of Madras as it was for the Founding Fathers of the United States.

Most of the small Armenian Diaspora of India in the 1700's were the descendents of the thousands of Armenians who were brought to Persia by Shah Abbas and settled in New Julfa (Nor Jugha) in 1605. They were traders who had moved to India in search of wealth and fortune. Many were rich and successful. They were free, yet, in some way, deep inside, homeless.

The feeling of being in the minority, with no state of their own, led to the formation of a movement which believed in organized action and unity in ranks as the best safeguards against outside forces, including assimilation. But unlike the traditional Armenian political parties which were formed in the early 1900's, the so-called "Madras Group" did not evolve into a political party.

Several books written in classical Armenian and published in Madras between 1772 and 1783 by this group of Armenians clearly reflect the anxiety of a Diaspora community which saw the dangers of assimilation and the threat of losing its identity, especially when it came to the younger generation of that time. The first of those books, which is called Nor Dedrag - Hortorag, or a book of guidelines and advice, was put together by a group of Madras businessmen, but carried the name of Movses Paghramian as its main author.

The book reflects the thinking and aspirations of the "Madras Group", and in effect is a detailed account of who the Armenians were, their roots, their history and more importantly where the nation was going after losing its statehood and living not only under occupation, but in a Diaspora.

In one chapter, the author lists the names of all the Armenian towns and villages as they existed in the 1700's. For Nagorno Karabakh, which was semi-autonomous and ruled by Armenian princes at the time, the list includes 14 villages and one city. For Persia, the birthplace of most of the members of the "Madras Group," the list includes 19 villages and six cities. For Cilicia, which was under Ottoman rule, the list mentions 19 villages and 12 cities. In all, the author says, there were 258 Armenian villages and 103 cities inhabited by Armenians - all in what used to be historic Armenia.

Outside of what Hortorag considers Hayots Ashkharh, or the Armenian world, it lists Armenian Diaspora communities in Moldova, Poland, Transylvania and Crimea and estimates the overall Armenian population of the 1700's to be a little over 5 million.

From the first page of Hortorag Paghramian and the others spell out the reasons for such a publication and underline the importance of efforts to prevent the new generation of Armenians from dropping its guard and falling prey to the slippery slope of assimilation. In its opening chapters, Hortorag gives a detailed description of all the early Armenian Kingdoms, its rulers, and tries to analyze why the nation lost its sovereignty and statehood.

Turning to the reasons of the "calamity" facing the Armenian nation in the 1700's, the book lists "corruption" and the "autocratic nature" of past administrations which, it said, left no room for individuals to have a say in government. "The mistake of an ordinary citizen can lead to his own personal loss and suffering, but if a Prince or a King makes a mistake, the whole nation will suffer and pay the price."

Outlining the shortcomings of past rulers, the book suggests several remedies including the need for education, opening of schools, raising the self-awareness and self esteem of the youth and "planting the seeds of nationalism" in the new generation of Armenians.

Bold concepts, especially given the fact they were put forward and advocated more than 200 years ago.

About the same time of the publication of Hortorag a more powerful book hit the Madras Armenian Diaspora scene. It was called Vorokayt Paratz, the challenges of glory, which gave the concept of statehood a new meaning.

Written by Hagop Shahamirian and published also in Madras in 1773, Vorokayt Paratz, and its addendum which was completed a few years later, not only outlined the future constitution of a free and independent Armenian state, but also created a set of by-laws for the Diaspora to govern itself with until the establishment of a such a state.

For the first time in Armenian history, it was Shahamirian who called for a "constitutional republic" as the best way of maintaining democracy and equality in the free Armenia of his dream. In great detail, Shahamirian explains how a "President should be elected by the people for a three year term and the President should be the head of the executive power."

It goes on to say that the future Armenian republic should "guarantee the freedom of conscience, and make every effort to separate church from state." Addressing his readers, Shahamirian says: "Fellow civilians, do not interfere in the affairs of the church. Clergy, do not interfere in the affairs of the civilians."

Turning to administrative matters, he calls for "all top government officials to be elected by the people. The country must have a 90,000-strong permanent army, and the state budget should come from various forms of taxation, based on the principle that the rich will have to give more than the poor."

On other issues, Vorokayt Paratz calls for an end to old hierarchy and replacing them in a democratic society with equality for all where every Armenian, and especially those living in the Diaspora, will make an annual financial contribution to a unified national fund.

"All citizens should have equal rights. Deeds should come before lineage. A faithful shepherd who protects his flock against wolves is a better man than a lazy Prince," Shahamirian wrote in 1773.

But what they created were not just concepts. The "Madras Group" also set up a special fund created through direct charitable donations from the community to establish schools, preserve the national heritage and culture and "make sure that Armenians of the Diaspora are not lost through assimilation."

"We should continue along this path of self reliance (in the Diaspora) until that blissful day, God willing, when our country will have its own ruler and the Armenians return to Mother Armenia and the arms of our Araratian home," Shahamirian and his friends wrote.

Along more practical terms, Shahamirian stressed the paramount importance of laws to govern all societies, starting from the community level up to the future Armenian State. "Where there are no laws, there will be no justice, no equality and no freedom. The people are the rulers and the King is the law," he wrote, explaining the essential need to create a society where the law is above all. "But the laws should come from the people and all should be equal under the law."

Having created a vision of how they saw a future state, Shahamirian and his fellow members of the "Madras Group" also realized that while Armenians had to mobilize their own efforts, they could not create a free Armenia without help. For them the key to such a state was in an alliance with Imperial Russia and neighboring Georgia-both Christian nations-along with the active help and support of the Armenian Princes of Nagorno Karabakh-or Meliks as they were known the time.

It is ironic that the early architects of an independent Armenian state believed that Nagorno Karabakh was as much a key issue as it is today, with the difference that it was Armenia which needed help.

The "Madras Group" was so fervent that one of its members, a merchant by the name of Khojah Krikor, offered to give all his personal wealth to finance the liberation of Armenia from foreign occupation-provided the endeavor had the support of the Holy See of Etchmiadzin. But indications, as seen in various publications from that era, were that Etchmiadzin was reluctant to give its blessing to a revolutionary movement against Ottoman Turkey and Persia, the superpowers of the region.

The "Madras Group" also offered financial help to Hovsep Emin, a prominent member of the Indian Armenian community who had spent most of his adult life in England and toured both Russia and Georgia, to organize the liberation movement.

In later years, Emin, in his memoirs, reflecting his disappointment with the lack of progress, writes: "Our people are shedding their blood and tears for a piece of bread. But as soon as a few people get rich, they are always subjected to pressures by outsiders because we do not have the strength to fight back and a country to stand behind us."

More than 200 years have passed since the birth of the "Madras Group." They did not see their dreams come true, but today Armenia is a free and independent republic and Shahamirian and his friends from Madras, India, can be remembered as early visionaries.

The Bells of St. Astvatzatzin

Church and belfry testament to a proud past long gone

St. Astvatzatzin Armenian Church, one of the oldest Christian structures in all of India and the Far East is located in Chennai (formerly Madras).

It was built in 1772 on the grounds an ancient Armenian cemetery that later became the private property of the Shahamirian family.

The church replaced an Armenian chapel that had been built in 1712 that was destroyed in the 1746 British-French colonial war. There are two dates inscribed at the church entrance – 1772 1nd 1712. The new construction was financed by Shahamir Shahamirian (Sultanumian) in memory of his wife who had died at an early age.

St. Astvatzatzin (Holy Mother of God) is a testament to the glorious history of Armenians in Madras. One can say that the entire legacy of Armenian Madras, that had become the foundry of the new liberation thought of the times, has been stored under the arches of this magnificent church.

St. Astvatzatzin is resting place for many historic figures

The white-plastered church is located on a street where the noted merchants Shahamir Shahamirian, Samuel Moorat, the Gregory Brothers, Seth Sam returned after their long and arduous journeys and found eternal rest.

The white-plastered church is located on a street where the noted merchants Shahamir Shahamirian, Samuel Moorat, the Gregory Brothers, Seth Sam returned after their long and arduous journeys and found eternal rest.

This is where the Madras Group was formed. Its members, including Movses Baghramian, Shahamir Shahamirian and Joseph Emin, soared no efforts to inculcate Armenian youth with ideals of enlightenment and progressive thought.

Under these arches, every Sunday for forty consecutive years, Father Harutiun Shmavonian, publisher of the first Armenian periodical “Azdarar” (Monitor), offered the Holy Liturgy.

At least two Armenian printing presses were started here in Madras, and an Armenian school. Many of the notable members of the Madras Armenian community were laid to rest here. No wonder the street is named “Armenian Street”.

At least two Armenian printing presses were started here in Madras, and an Armenian school. Many of the notable members of the Madras Armenian community were laid to rest here. No wonder the street is named “Armenian Street”.

Time has marched on and there are no longer any Armenians in Madras. But the walled Armenian Church, symbolizing their eternal glory rises proudly on a hill top. At first glance, it is hardly noticeable.

When bells ring locals know an Armenian has returned

The commercial shopkeepers that line the street know precious little about the church. But they are aware that it’s the oldest Christian cathedral in the district.

Few also know that the unique and valuable examples of the first Christian bells forged rest here in the church, in the three story bell tower that rises apart from the church.

The belfry’s three pair of enormous bells called the faithful to church for many decades. Sadly, now the bells are not rung every Sunday. When the peeling of the bells is heard, residents in the vicinity of Armenian Street know that an Armenian has come to the church. Most Armenian visitors today come from Calcutta. The bulk of Madras Armenians relocated to Calcutta in the latter half of the 19th century.

Each pilgrim that visits the Armenian church climbs the tower to see the bells and to capture the moment. All three pairs of bells bear dates. Each weighs 150 kilos. The oldest was forged in 1754.

Each pilgrim that visits the Armenian church climbs the tower to see the bells and to capture the moment. All three pairs of bells bear dates. Each weighs 150 kilos. The oldest was forged in 1754.

Armenian church bells bear proud legacy

This bell has an Armenian inscription that was added in 1808 at the district’s famous “Aroulapan” foundry. The next bell was forged in 1778 and the other two in 1790. They were donated by Agha Shahamir Shahamirian in memory of his son Eliazar Shahamirian who died at the tender age of nineteen. The last pair of bells is the most valuable, having been forged in 1837 with the inscription, “Thomas Mears, Founder, London”. This signifies that the bells were built at the prominent Whitechapel Bell Foundry in London. This foundry entered the Guinness Book of records as the oldest manufacturing concern in Great Britain. It mostly produces bells for use in churches.

The foundry has been operating since 1420. Traditionally, the name of the chief craftsman of the period would be engraved on the bells produced. From the 19th century up till 1968, all the finished products, including the bells of St. Astvatzatzin, have carried the moniker of “Mears & Stainbank”

The oldest bell forged at this foundry is kept in London. It has the dubious distinction of being the world’s oldest. The next bell with the oldest inscription is the famous Philadelphia Liberty Bell, dated 1752.

The Liberty Bell epitomizes the American War of Independence from Britain. Tradition has it that the bell signaled the signing of the American Declaration of Independence in 1776. Every year, thousands of visitors flock to Philadelphia to gaze at this historic and valuable bell.

Perhaps the most famous bell produced at this foundry is the one that rings in the Big Ben clock tower in London’s Westminster Palace. Forged in 1858, it is the biggest bell ever forged with a height of 2.2 meters and a width of 2.9. It weighs in at an astounding 13 tons.

Other famous bells to come out of the Whitechapel Foundry are those at the Liverpool Mother Cathedral, London’s St Mary le Bow Church and the bells at Westminster Abbey. Includes in this list of ancient bells are two of the six bells found in the St. Astvatzatzin Church in Madras.

While it’s nearly impossible to state with any certainty that purchased the bells for the church, by the application of a bit of deduction and cross-referencing of the dates on the bells with the wealthiest Armenians in Madras at the time, we can speculate that it was either the Gregory Brothers or Seth Sam. It’s less likely that the Moorat Family purchased the bells since they adhered to the Roman Catholic Church.

Naturally, these bells symbolize the dedication of the Armenians of Madras to the Armenian Apostolic Church. On the other hand, they also reflect the wealth and prosperity that the community possessed at the time.

This short narrative allows us to delve, albeit briefly, into the life and times of the Madras Armenian community.

The English historian J. Hanvey, discussing the Armenian merchants of Madras during the 18th century, notes that, “Armenians were successfully trading with Russia as well as with England. With their capital and contacts they held their own against the likes of English, Russian and Dutch traders.

We thus see that at the dawn of the 19th century, Armenian merchants, with their financial resources and prowess, were still giving the British East-Indian company a run for the money.

It is likely that with such investments in English manufacturing, the Armenians of Madras were aiming to preserve their influence in British controlled India.

Hermineh Adamyan Armenian College and Philanthropic Academy Calcutta (Kolkata), India

Armenian Heritage Ensemble

The Armenian Heritage Ensemble was established in Singapore in 2009 with a mission to highlight the history and culture of Armenia through the performing arts. Our inaugural performance in December 2009 was the first in a series of regular concerts and events held in conjunction with the Armenian Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator Singapore - Singapore's oldest standing Church built in 1835.

The Ensemble features accomplished Armenian musicians and artists, including (left to right): Gayane Vardanyan (vocals), Naira Mkhitaryan (piano), Chake Hovaghimian (recitation) and Ani Umedyan (violin), who take audiences on enchanting musical and poetic journeys to Armenia and beyond. Past programmes have included works by noteworthy Armenian artists such as: Baghdassarian, Khachaturyan, Komitas, Paruyr Sevak, Silva Gaboudikian, Babajanyan and Gevork Emin. The Ensemble's repertoire also includes works by favorite Western composers, including: Albinoni, Bach, Verdi, Piazzolla, Tchaikovsky and more.

The Armenian Heritage Ensemble performs quarterly, and each concert is centered around a special theme in Armenian culture and life. All proceeds from the concerts are donated to the Armenian Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator Singapore.

Past performances:

24 APRIL 2010: Honouring the Victims of the Armenian Genocide 1915

10 DECEMBER 2009: A Special Evening of Classical Music & Poetry

Useful Links About Armenia

Religion

Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin

Worldwide Directory of Armenian Churches

Government

The Government of the Republic of Armenia

Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Armenia

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia

Ministry of Diaspora of the Republic of Armenia

News & Research

Armenpress Armenian News Agency

Armenian Directory Yellow Pages

Respected Citizens: The History of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia

Organisations

Armenian General Benevolent Union

Tourism

Armenian History Remnants in Kolkata

| By Leonard M Apcar, International Herald Tribune | |

| Today, there are only a few hundred Armenians in the entire Kolkata region... | |

|

Before there were call centres and Indian conglomerates, before the East India Company or the British Raj, there were Armenians who made their way to India to trade and to escape religious persecution from the Turks and, later, Persians.

Entrepreneurial and devout Christians, Armenians arrived in northeast India in the early 1600s, some 60 years before British adventurers became established traders in Kolkata. They acquired gems, spices and silks, and brought them back to Armenian enclaves in Persia such as Isfahan. Eventually, some Persian Armenians — including my ancestors — left and set up their own businesses and communities here, landing first on India’s western flank in Surat and nearby Bombay, the present-day Mumbai, and then moving to the river banks in northeast India that led to Kolkata’s founding as a sprawling manufacturing and port city. Kolkata’s vast manufacturing centres rivalled the English Midlands, and wealth flowed freely to Jews, Britons, Armenians and some Indians. They in turn poured money into elaborate colonial mansions, Victorian memorials and a luxurious Western way of life virtually transplanted to the wilting jungle of West Bengal. The British are gone now, of course, and that way of life is literally crumbling in the dusty, clogged streets of Kolkata. All but gone, too, are the Armenians who began leaving India long before the British. But last week Armenians with Kolkata roots gathered here again from around the world. More than 250 people came officially for the 300th anniversary of the oldest church in Kolkata, a finely preserved Holy Church of Nazareth tucked inside the narrow, winding alleys and chaotic bazaars of the north section of this city. But they also came to be together again and to honour an extraordinary restoration effort of all five Armenian churches and assorted graveyards in northeast India. I came from Hong Kong, but many came from England, Iran, the United States and Australia. We walked the cemeteries looking for graves of grandparents and great-grandparents, toured the 187-year-old Armenian school, admired the ambitious renovation work recently completed on the churches and cemeteries and at the gleaming white church in downtown Madras. Armenians never amounted to more than a few thousand people in Kolkata, but in the 18th and 19th centuries they ran trading companies, shipping lines, coal mines, real estate developments and hotels. A few served in the colonial government, and some had sewn themselves so finely into the fabric of colonial India that they were decorated with British titles and were leaders of private English-only clubs. By the time the British left, and an independent India was on a socialist and anti-colonial bent, the Armenians had mostly cleared out. Wealthier, educated and more confident as entrepreneurs, they left not for Armenia itself, then a Soviet-controlled postage stamp of a state, but for London, where some Kolkata Armenians had second lives, or new frontiers in Australia or the US. Armenian churches and graveyards dot India in Agra, Delhi, Hyderabad, Chennai, Mumbai, Surat and, of course, Kolkata. But they are also in Dhaka, Bangladesh; Yangon in Myanmar; on Penang Island off the coast of Malaysia; Singapore; and parts of Indonesia — all places where Armenians settled, traded and worshiped. Worship is the social adhesive that binds Armenians together. Clannish and wary of outsiders, the church has always been the focus of their socialist and cultural lives. Given Armenia’s pride as the first state to adopt Christianity as its religion, it was not surprising that last week with the families came Karekin II, Catholicos of all Armenians, as the leader of the Holy Armenian Apostolic Church is known, and a choir of two dozen from the church’s seat in Etchmiadzin, Armenia. But the real stars in Kolkata were its five churches. Only a few years ago four of them were weed-infested snake pits looking like Roman ruins. Now, in the midst of southeast Kolkata’s horrid slums, on gritty, rutted roads, rises Holy Trinity Chapel in the Tangra district with a new dome and a manicured graveyard. Inside, I found the refurbished graves of my great-great grandparents, who in the 1880s lived in Kolkata and Rangoon, as Yangon was known then. Richard Hovannisian, a historian and professor of Armenian studies at the University of California at Los Angeles, said what distinguished the Armenian diaspora in India was that the Armenians never accompanied their trading ambitions with military force. Nor did they try to enforce cultural supremacy. As Indians took control of their country, Armenians were looked on as holdovers from a colonial past. Many large Armenian family enterprises in India were either sold off or closed. Today, there are only a few hundred Armenians in the entire Kolkata region. The Armenian school here has long relied on students from abroad to fill its dormitories. While the Armenian community in Kolkata has all but disappeared, there is hardly a serious guidebook or history book of the city that does not mention their influence, charities and churches. That is a source of pride and communal strength reflected in last week’s commemoration. |

|

АРМЯНЕ В СИНГАПУРЕ

Это продолжение темы: Церковь Григория Просветителя в Сингапуре

После написания поста Սուրբ Գրիգոր Լուսաւորիչի Եկեղեցի об армянской церкви в Сингапуре меня заинтересовало, как армяне попали в Сингапур и как они там жили. С помощью интернета удалось найти довольно интересные материалы.

"Процветавшие в Индии армянские купцы оказали большие услуги в утверждении здесь британской Ост-Индской компании, взамен британцы предоставили им те же привилегии, что и своим собственным купцам. Голландская Ост-Индская компания со штаб-квартирой в Батавии также разрешила армянским купцам свободно торговать под своей защитой. Неудивительно, что армяне селились в торговых портах и городах, находящихся под контролем этих двух главных сил — там, где они рассчитывали на долгосрочную безопасность."

- получилось слишком длинно, но факты интересные! -

Армянская община в Сингапуре образовалась позже других армянских общин в Юго-Восточной Азии — ранее были основаны общины в Бирме, Голландской Восточной Индии и Пенанге. Среди множества сингапурских поселенцев, прибывших из разных уголков земного шара, армяне составляли незначительную группу. Сами они или их родители были выходцами из Персии, главным образом из Нор-Джуги и прибывали в Сингапур из Мадраса, Калькутты, с острова Ява. С 1820 года по 2002 в Сингапуре проживало в общей сложности 656 армян, причем только 462 из них дольше пяти лет. При этом армянам довелось сыграть значительную роль в жизни колонии и оставить о себе память, несопоставимую с их малой численностью.

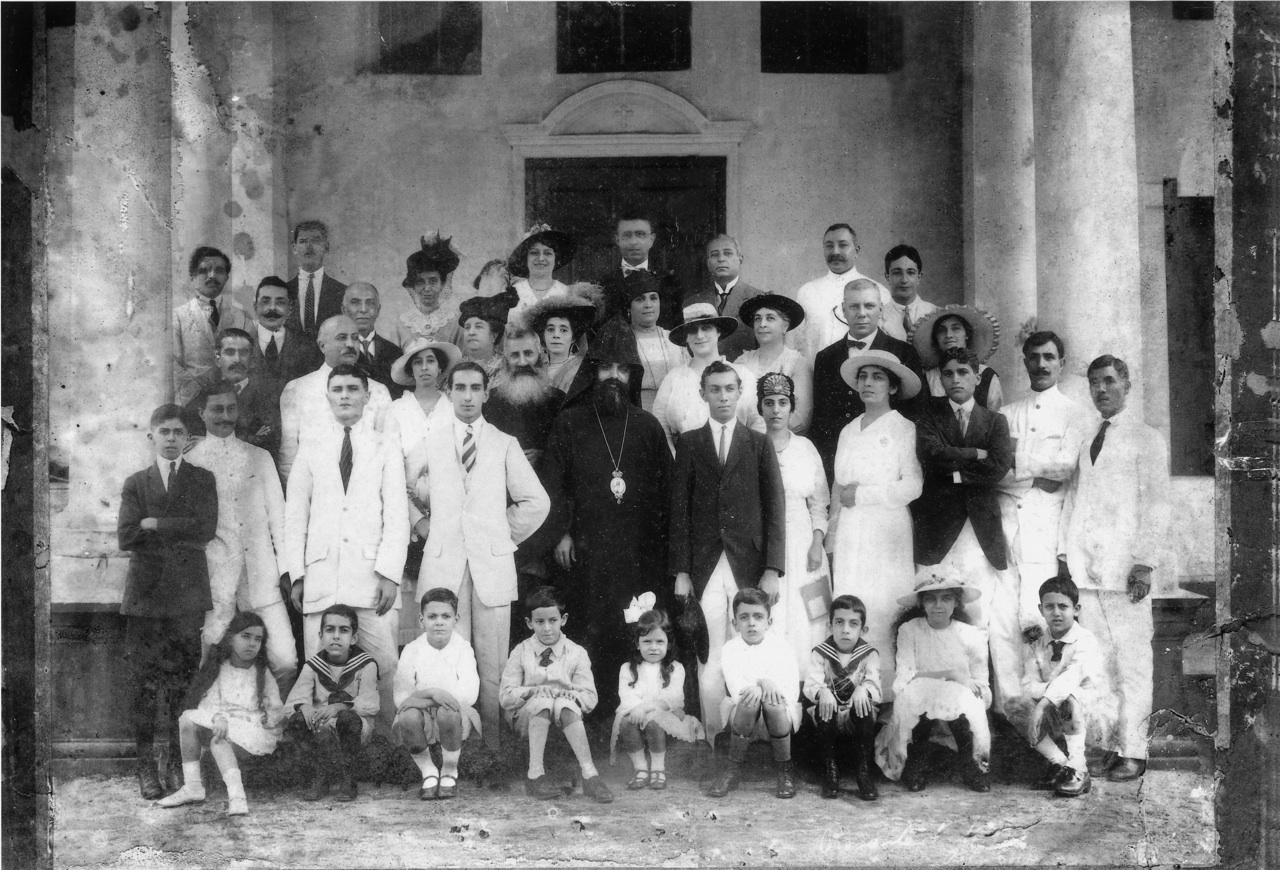

Представители армянской общины Сингапура. Фото 1917 год

Представители армянской общины Сингапура. Фото 1917 год

В 1834 году в Сингапуре насчитывалось 44 армянина и 138 выходцев из Европы — максимальное соотношение за всю историю колонии. В отличие от арабских и китайских торговцев, армянские привозили свои семьи, рассчитывая при благоприятных обстоятельствах пустить здесь корни. С самого начала они активно участвовали в жизни местного общества. В 1836 году была освящена церковь Сурб Григор Лусаворич, выстроенная годом раньше в стиле неоклассицизма усилиями крохотной армянской общины. Первая христианская церковь в Сингапуре, она стала также первым зданием в колонии, где в 1909 году было установлено электрическое освещение. На сегодняшний день это одна из двух армянских церквей, сохранившихся в Юго-Восточной Азии, вторая находится в столице Бирмы Рангуне. Церковь не только удовлетворяла религиозные потребности, но и поддерживала единство общины за счет совместного участия в крестинах, свадьбах, похоронах. Сюда поступали из Эчмиадзина новости о событиях в Армении. При посещении Сингапура в 1917 году епископ Торгом Гушакян с удивлением обнаружил, что не нуждается в услугах переводчика — родившиеся здесь армяне знали родной язык.

Армянская церковь в Сингапуре.

Армяне Сингапура большей частью занимались торговыми операциями, их привлекал сюда статус "порто-франко". Из 113 армянских предприятий, зарегистрированных с 1820 года, 63 были торговыми. Первым армянским купцом в Сингапуре был Аристакес Саркис, он поселился здесь в 1820 году. В коммерческой палате Сингапура, основанной в 1837 году, состояли шесть британцев, два китайца, один американец, один араб и один армянин — Исайя Закария.

В ранние годы существования колонии армяне помогли Сингапуру стать крупным транзитным центром. После того, как торговля с Борнео прервалась из-за вооруженных беспорядков на самом острове и пиратства в прибрежных водах, Галстан Мозес был первым, кто послал туда корабль в 1834 году. Сам Галстан и капитан корабля были любезно встречены раджой и смогли восстановить торговлю — корабль вернулся с грузом перца, золотой пыли, бриллиантов и камфары. Вслед за этим и другие сингапурские купцы отправили на остров свои суда.

Армянская церковь в Сингапуре.

Армяне Сингапура большей частью занимались торговыми операциями, их привлекал сюда статус "порто-франко". Из 113 армянских предприятий, зарегистрированных с 1820 года, 63 были торговыми. Первым армянским купцом в Сингапуре был Аристакес Саркис, он поселился здесь в 1820 году. В коммерческой палате Сингапура, основанной в 1837 году, состояли шесть британцев, два китайца, один американец, один араб и один армянин — Исайя Закария.

В ранние годы существования колонии армяне помогли Сингапуру стать крупным транзитным центром. После того, как торговля с Борнео прервалась из-за вооруженных беспорядков на самом острове и пиратства в прибрежных водах, Галстан Мозес был первым, кто послал туда корабль в 1834 году. Сам Галстан и капитан корабля были любезно встречены раджой и смогли восстановить торговлю — корабль вернулся с грузом перца, золотой пыли, бриллиантов и камфары. Вслед за этим и другие сингапурские купцы отправили на остров свои суда.

В 1830–50-х годах армянские компании в Юго-Восточной Азии доминировали в торговле сурьмой — редким металлом, поставлявшимся в Англию. Начиная с 1850-х годов индийские армяне играли ключевую роль в торговле опиумом, который тогда был веществом, легально применявшимся в медицинских целях. Корабли судоходной компании "Апкар" доставляли опиум из Индии в Китай, разгружая по пути в сингапурском порту поставки товара на консигнацию. Армяне, в особенности Мартирос Карапет, были главным импортерами опиума в Сингапуре до конца 1880-х годов, когда торговля этим веществом перешла к еврейским фирмам.

Случалось, армянские купцы находили нужным объединиться — так, одна за другой, были основаны четыре армянские фирмы: "M&G Moses" (1839), "Sarkies&Moses" (1840), "Set Bro-thers" (1840), "Stevens&Joaqim" (1848). Для транспортировки товаров обычно пользовались морским перевозчиком "Apcar&Company" — это предприятие находилось в Калькутте и осуществляло рейсы между Сингапуром, Пенангом, Индией и Китаем. Армянские купцы предпочитали судна, принадлежащие армянам, с армянскими капитанами — такие, как парусный барк "Тенассерим" (капитан Саркис), корабли "Черкес" и "Леди Каннинг" (капитан Галстан). Многие морские суда носили армянские имена: "Армения", "Арарат", "Мэри Макертум", "Джозеф Манук", "София Джоаким", "Аратун Апкар", "Григор Апкар".

В 1830–50-х годах армянские компании в Юго-Восточной Азии доминировали в торговле сурьмой — редким металлом, поставлявшимся в Англию. Начиная с 1850-х годов индийские армяне играли ключевую роль в торговле опиумом, который тогда был веществом, легально применявшимся в медицинских целях. Корабли судоходной компании "Апкар" доставляли опиум из Индии в Китай, разгружая по пути в сингапурском порту поставки товара на консигнацию. Армяне, в особенности Мартирос Карапет, были главным импортерами опиума в Сингапуре до конца 1880-х годов, когда торговля этим веществом перешла к еврейским фирмам.

Случалось, армянские купцы находили нужным объединиться — так, одна за другой, были основаны четыре армянские фирмы: "M&G Moses" (1839), "Sarkies&Moses" (1840), "Set Bro-thers" (1840), "Stevens&Joaqim" (1848). Для транспортировки товаров обычно пользовались морским перевозчиком "Apcar&Company" — это предприятие находилось в Калькутте и осуществляло рейсы между Сингапуром, Пенангом, Индией и Китаем. Армянские купцы предпочитали судна, принадлежащие армянам, с армянскими капитанами — такие, как парусный барк "Тенассерим" (капитан Саркис), корабли "Черкес" и "Леди Каннинг" (капитан Галстан). Многие морские суда носили армянские имена: "Армения", "Арарат", "Мэри Макертум", "Джозеф Манук", "София Джоаким", "Аратун Апкар", "Григор Апкар".

армянский торговый корабль в Индийском Океане (гравюра)

Торговые операции были не единственным видом деятельности. В 1880-х годах армяне играли ключевую роль в создании трех из четырех недолговечных страховых компаний. Семья Мозес занималась ювелирным делом и ремонтом часов, в 1920-х дилеры по торговле бриллиантами братья Ипекчян открыли отделение в Сингапуре. Мозес Мозес и Джордж Майкл владели главными сингапурскими фотоателье с начала 1880-х до 1920-го года. Джо Джоаким работал директором компании по разработке рудников и добыче олова. Директорами горнодобывающих компаний были Питер и Кут Эдгары. Среди армян были также врачи, юристы, клерки, инженеры, музыканты.

Однако наибольших успехов армяне добились в сфере обслуживания: они владели одиннадцатью отелями (в том числе крупнейшими), а также многими пансионами и ресторанами. Первым армянином — содержателем гостинцы в Сингапуре стал Малькольм Мозес, в 1862 году он приобрел в собственность отель "Pavilion". Одним из самых успешных армянских предприятий в Сингапуре был отель "Raffles", открытый братьями Саркис в 1887 году. В 1903 году Аратун Саркис и Егиазар Иоханнес приобрели отель "Adelphi". Новые хозяева "Hotel de l'Europe", перестроившие его в 1904 году, также были армянами. Загородный курортный отель "Sea View" с 1912 по 1921 годы принадлежал Егиазару Йоханнесу, затем был приобретен братьями Саркис. Армяне часто пользовались услугами отеля "Raffles". Нуждаясь в адвокате, они обращались в первую очередь к братьям Джоаким, позднее к Мак Йоханнесу и Кеннету Сету.

Армянские предприниматели сдавали друг другу внаем собственность, приобретали долю в армянских компаниях, нанимали соотечественников на работу. Помогали тем, для кого наступали трудные времена — выдавали поручительства, акцептовали векселя, сужали деньги, часто под одно только честное слово. Даже церковь Сурб Григор Лусаворич в трудные для отеля "Раффлс" времена приобрела акции компании, предоставив владельцам необходимую наличность.

Несмотря на свою малочисленность, армяне выдвигались и на политическом поприще. В 1895 году двое из восьми муниципальных уполномоченных были армянами. Большое достижение, с учетом того, что из 972 голосовавших, насчитывалось только 25 армян, среди 522 потенциальных кандидатов их было только трое. В 1887 году Джо Джоаким был избран президентом муниципального совета, затем избирался в Законодательное собрание.

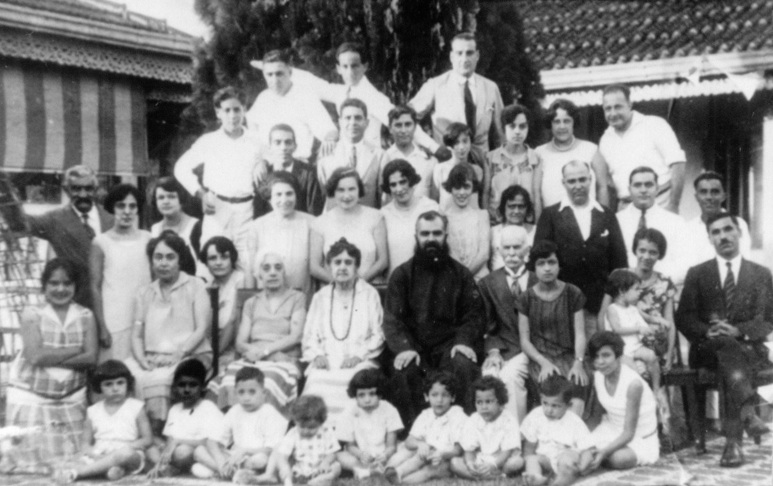

Руководство компании "Edgar Brothers". Фото 1929 год.

Руководство компании "Edgar Brothers". Фото 1929 год.

В некоторых случаях армянские предприниматели стремились публично подчеркнуть свою национальную принадлежность. Например, Кэтчик и Мэри Мозес однажды появились на костюмированном балу в одеждах киликийского царя Левона и царицы Марии. Тот же Кэтчик назвал свою первую резиденцию "Гора Арарат", а Парсик Иоахим — "Гора Наркис". Однако в административной практике определение "армянин" иногда вызывало проблемы. Например, в 1925 году чиновник колониальной администрации объявил Джорджу Эдгару и его родителям, что международное право не предусматривает такой национальности, поскольку не существует государства Армения. В результате для Джорджа в графе национальность было проставлено "неопределенная", а для его родителей — "оттоманская".

В 1845 году Кэтчик Мозес основал англоязычную газету "Straits Times", четыре года спустя Грегори Галстан — армянскую газету "Усумнасер".

Местная пресса сообщала о резне армян в Оттоманской империи при султане Абдул-Гамиде. В декабре 1894 был организован Комитет помощи с участием, как армян, так и граждан других национальностей. Щедрыми были пожертвования и в 1915 году, когда стали поступать известия о начале полного истребления армян в восточных вилайетах. По инициативе епископа Торгома Гушакяна в 1917 году в Сингапуре было основано отделение Армянского Всеобщего Благотворительного Союза.

Армянская община Сингапура поддерживала прочные связи с ближайшими общинами, в особенности с Калькуттой, где большинство имело родственников или друзей. Из Калькутты доставлялись роскошные свадебные торты, оттуда везли и мраморные надгробия, украшенные резьбой по камню. Тесными были дружеские и деловые связи с армянами Голландской Восточной Индии.

Одна из проблем сохранения любого национального меньшинства — недостаток потенциальных партнеров для брака внутри сообщества. Питер Сет и Макертич Мозес из первой волны переселенцев отправились искать жен-армянок в Индию. Позже Регина Джоаким, Эмили Иоханнес, Аристакес Мозес и Манук Мозес нашли себе пару в армянской общине острова Ява. Однако гораздо чаще супруг или супруга выбиралась за пределами национальной среды. Так поступили трое сыновей Захарии в 1850-х и четверо из пятерых братьев Джоаким.

Отпрыски армян неизменно выделялись успехами в учебе. В конце 1830-х годов несколько армянских учеников — Якоб и Джон Иоханнес, Якоб Шамир и Грегори Захария получали большинство ежегодных наград, в сороковые годы армянские учащиеся все еще доминировали в списке награжденных. Некоторые дети обучались в Калькутте — в Армянском училище и школе "La Martiniere", с 1880-х годов состоятельные армянские семьи отправляли детей учиться в Англию — в колледжи Брайтон, Сент Пол, Херн, Челтенхем и другие. Богатые армяне состояли членами сингапурского яхт-клуба, Джо Джоаким был членом Комитета морского спорта, который устраивал парусные гонки. Армяне увлекались крикетом, популярным в Британии и колониях. Ярым любителем скачек слыл Тигран Саркис со своими шестью лошадями. В 1904 году они принесли ему 1400 долларов по тогдашнему курсу, выведя на третье место среди всех владельцев. Особенно удачным был 1908 год, когда конь по кличке Джилло взял Кубок губернатора. Армянки составляли серьезную конкуренцию другим участницам цветочных выставок. Большую часть 1890-х годов призы за свои растения получали Мэгги Чэйтер, Ирен и Рипси Иоханнес, но доминировали женщины разных поколений из семьи Джоаким, получившие в 1897 году 18 из 104-х призов. В истории страны осталась армянка Агнес Джоаким, которая вывела сорт орхидей "Ванда мисс Джоаким". В 1947 году этот удивительно красивый цветок был выбран эмблемой Прогрессивной партии, а в 1981 году — национальным цветком, символом всего Сингапура.

Помня о своем происхождении, армяне Сингапура всегда были лояльными гражданами Британской империи. (Сингапур был британской колонией с 1824 года .) Уроженцы Персии натурализовались в качестве граждан Великобритании, их дети, рожденные в Сингапуре, приобретали гражданство с рождения. Со временем армянские компании Сингапура стали открывать свои отделения и представительства в Лондоне, Манчестере, Ливерпуле. В 1887 году, в поздравительном послании королеве Виктории по случаю пятидесятилетия ее правления 26 видных представителей общины сообщали, что она всегда может положиться на благодарность и верность своих армянских подданных в Сингапуре: "верность, имеющая столь прочную основу, будет существовать всегда, пока не угаснет армянская нация". В церкви Св. Григора была проведена специальная юбилейная служба. Армяне щедро жертвовали средства в юбилейный фонд, а через десять лет столь же щедро вносили деньги на сооружение памятника королеве.

Армениан Стрит. Фото 1895 год.

Армениан Стрит. Фото 1895 год.

С началом второй мировой войны молодые армяне отправились служить в британскую армию и подразделения местных волонтеров. За счет Осепа Аратуна был построен и оснащен самолет-разведчик для британских военно-воздушных сил. На боевые самолеты жертвовали средства и другие армянские предприниматели. Некоторым армянским семьям удалось эвакуироваться в Австралию перед захватом Сингапура японцами. Остальные, как британские подданные, были интернированы в лагеря, где много людей погибло от тяжелых условий содержания. Армянская община Сингапура никогда не смогла оправиться от потерь, понесенных во время войны. По данным переписи 1947 года в стране с населением около миллиона человек насчитывалось всего 62 армянина.

Главным фактором упадка общины была, конечно, ассимиляция. Она не встречала больших препятствий, поскольку армяне были христианами и принадлежали к индоевропейской расе. Часто брак был первой ступенью к утрате армянского наследия. Те, кто сочетались браком с англичанами или англичанками, воспитывали детей в британском духе. Дети не владели армянским языком, не посещали армянскую церковь, не имели армянских имен — окружающие вообще не воспринимали их как армян. Другой причиной была постоянная миграция. Одна семья приезжала, другая отбывала навсегда — начать бизнес в новом месте, вернуться в Персию, перебраться в Индию или Англию. После войны условия для бизнеса в Сингапуре оказались не слишком благоприятными. Гораздо более перспективным местом выглядела Австралия, где быстрыми темпами росла армянская община Сиднея. К концу 50-х годов стало ясно, что развивается новый Сингапур, где будущее армян выглядит очень туманным. Немногочисленная община стала быстро таять.

Ее главным вкладом в жизнь страны можно считать церковь Сурб Григор, признанную городской достопримечательностью, национальный цветок Сингапура "Ванда мисс Джоаким" и процветающий отель "Раффлс" с уникальной международной репутацией. О времени армянского присутствия в Сингапуре свидетельствуют и сохранившиеся названия четырех улиц: Армениан стрит, Галстан авеню, названная в честь Эмиля Галстана, Саркис роуд — в честь Регины Саркис и Сент Мартин драйв, появившаяся при разделе "Эксбанка" — собственности Мартина. Армениан лэйн и Наркис роуд исчезли с карты в результате нового строительства.

От армян остались и памятники на городском кладбище. В 1970 году, когда правительство Сингапура решило его благоустроить, американец Левон Пальян, работавший в то время в Сингапуре, поставил себе целью разыскать как можно больше армянских могил, чтобы они не исчезли в результате строительных работ. Он получил разрешение перенести захоронения к церкви Сурб Григор, и теперь могилы многих из вышеназванных армян можно увидеть в небольшом мемориальном саду за церковным зданием.

материалы:

- книга "Респектабельные граждане" Нади Райт

- журнал "Анив"

Bangladesh's Last Armenian Prays For Unlikely Future

Bangladesh's Last Armenian Prays For Unlikely FutureBy Shafiq Alam, AFP

Michael Joseph Martin is guarded about his exact age and reluctant to accept he will be the last in a long line of Armenians to make a major contribution to the history of Bangladesh.

Dhaka, the Bangladeshi capital, was once home to thousands of migrants from the former Soviet republic who grew to dominate the city's trade and business life. But Martin, aged in his 70s, is now the only one left.

"When I die, maybe one of my three daughters will fly in from Canada to keep our presence here alive," Martin said hopefully, speaking broken Bengali with a thick accent.. "Or perhaps other Armenians will come from somewhere else."

Martin came to Dhaka in 1942 during World War II, following in the footsteps of his father who had settled in the region decades earlier. They joined an Armenian community in Bangladesh dating back to the 16th century, but now Martin worries about who will look after the large Armenian church in the city's old quarter.

"This is a blessed place and God won't leave it unprotected and uncared for," he said of the Church of Holy Resurrection, which was built in 1781 in the Armanitola, or Armenian district.

Martin -- whose full name is Mikel Housep Martirossian -- looks after the church and its graveyard where 400 of his countrymen are buried, including his wife who died three years ago. When their children, all Bangladeshi passport-holders, left the country along, Martin became the sole remaining Armenian here. He now lives alone in an enormous mansion in the church grounds.

"When I walk, sometimes I feel spirits moving around. These are the spirits of my ancestors. They were noble men and women, now resting in peace," said Martin, who is stooped and frail but retains a detailed knowledge of the Armenian history in Dhaka.

Marble tombstones display family names such as Sarkies, Manook and Aratoon from a time when Armenians were Dhaka's wealthiest merchants with palatial homes who traded jute, spices, indigo and leather. Among the dead are M. David Alexander, the biggest jute trader of the late 19th century, and Nicholas Peter Poghose who set up Bangladesh's first private school in the 1830s and died in 1876.

Martin, himself a former trader, said the Armenians, persecuted by Turks and Persians, were embraced in what is now Bangladesh first by the Mughals in the 16th and 17th centuries and then by the British colonial empire. Fluent in Persian -- the court language of the Mughals and the first half of the British empire in India -- Armenians were commonly lawyers, merchants and officials holding senior public positions.

They were also devout Christians who built some of the most beautiful churches in the Indian subcontinent. "Their numbers fluctuated with the prospects in trading in Dhaka," said Muntasir Mamun, a historian at Dhaka University.

"Sometimes there were several thousand Armenians trading in the Bengal region. They were always an important community in Dhaka and dominated the country's trading. They were the who's who in town. They celebrated all their religious festivals with pomp and style."

The decline came gradually after the British left India and the subcontinent was partitioned in 1947 with Dhaka becoming the capital of East Pakistan and then of Bangladesh after it gained independence in 1971.

These days, the Armenian Church holds only occasional services on important dates in the Orthodox Christian calendar, with a Catholic priest from a nearby seminary coming in to lead prayers at Christmas. Martin said the once-busy social scene came to a halt after the last Orthodox priest left in the late 1960s, but he is determined to ensure the church's legacy endures.

"Every Sunday was a day of festival for us. Almost every Armenian would attend the service, no matter how big he was in social position. The church was the centre of all activities," he said.

"I've seen bad days before, but we always bounced back. I am sure Armenians will come back here for trade and business. I will then rest in peace beside my wife."

Singapore Community Photos

The Armenian Apostolic Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator (Penang)

As yet no evidence of Armenian activity has been found in connection with Armenian Street. The Armenians in fact worshipped at St. Gregory's at Bishop Street, formerly located between King Street and Penang Street.

The Armenian Church of Penang was founded in 1822, more than a decade before the one in Singapore. In 1937, the church land was sold and the graves were transferred to a mass grave in the Western Road cemetery.

A prominent Armenian clan was the family of Arratoon Anthony. The Anthonys were among the Armenian diaspora that settled in Shiraz in Persia, and then in Bombay and Calcutta before coming to Penang.

But by far the most famous Armenians in the region were the Sarkies brothers who made their mark as hoteliers of the Eastern & Oriental in Penang and of the Raffles in Singapore.

|

At the same time, the Hokkien-dominated secret society called Khian Teik set up its base at the Tua Pek Kong Temple in Armenian Street. The Khian Teik allied itself with the Red Flag secret society - two chief of the latter were Syed Mohamed Alatas and Che Long who lived in Armenian Street. The whole area intensively built with institutional bases surrounded by the member's houses, was turn into Khian Teik Red Flag Stronghold. During the Penang Riots of 1867, the Khian Teik Red-Flag alliance fought with the Ghee Hin - White Flag alliance for control of Georgetown. Armenian Street was one of the centres of fighting, where Europeans volunteer police and their sepoys had to erect stockades. The entire town was laid siege for ten days, while reinforcements for both sides came from as far as Province Wellesley and Phuket. Over the next few decades, smaller clashes continued to occur, until secret societies were finally suppressed in 1890. By that time, the Khian Teik had asserted their control, which allowed the Hokkien traders to emerge as the dominent force in Penang. |

|

|

Row house along Armenian Street |

India

History

Armenians had trading relations with several parts of India, and by the 7th century a few Armenian settlements had appeared in Kerala, an Indian state located on the Malabar Coast. Armenians controlled a large part of the international trade of the area, particularly in precious stones and quality fabrics.

An archive directory (published 1956) in Delhi, India states that an Armenian merchant-cum-diplomat, named Thomas Cana, had reached the Malabar Coast in 780 using the overland route. Seven hundred years thereafter, in the year 1498, Vasco da Gama reached the Malabar Coast. Thomas Cana was an affluent merchant dealing chiefly in spices and muslins. He was also instrumental in obtaining a decree, inscribed on a copperplate, from the rulers of Malabar, which conferred several commercial, social and religious privileges for the Christians of that region. In current local references, Thomas Cana is known as "Knayi Thomman" or "Kanaj Tomma", meaning Thomas the merchant.

The Armenians in India can justly be proud of a glorious past but their present and future are not at all bright. They have greatly decreased in number. Now there are hardly 100 Armenians in India, mostly in Kolkata, where the Armenian College still functions.

Settlements

Several centuries of presence of Armenians, described as "The Merchant Princes of India”, resulted in the emergence of a number of several large and small Armenian settlements in several places in India, including Agra, Surat, Mumbai, Chinsurah, Candernagore, Calcutta, Saidabad, Chennai, Gwalior, Lucknow, and several other locations currently in the Republic of India. Lahore and Dhaka – currently respectively in Pakistan and Bangladesh, – but, earlier part of Undivided India, and Kabul, capital of Afghanistan, also had an Armenian population. There were also many Armenians in Burma and Southeast Asia.

- Akbar (1556-1605), the Mughal emperor, invited Armenians to settle in Agra in the 16th century, and by the middle of the 19th century, Agra had a sizeable Armenian population. By an imperial decree, Armenian merchants were exempted from paying taxes on the merchandise imported and exported by them, and they were also allowed to move around in the areas of the Mughal empire where entry of foreigners was otherwise prohibited. In 1562, an Armenian Church was constructed in Agra.

- During the 16th century onwards, the Armenians (mostly from Persia) formed an important trading community in Surat, the most active Indian port of that period, located on the western coast of India. The port city of Surat used to have regular sea borne to and fro traffic of merchant vessels from Basra and Bandar Abbas. Armenians of Surat built two Churches and a cemetery there, and a tombstone (of 1579) in Surat bears Armenian inscriptions. The second Church was built in 1778 and was dedicated to Virgin Mary. A manuscript written in Armenian language in 1678 (currently preserved in Saltikov-Shchedrin Library, St. Petersburg) has an account of a permanent colony of Armenians in Surat.

- The Armenians settled in Chinsurah, near Calcutta, West Bengal, and in 1697 built a Church there. This is the second oldest Church in Bengal and is still in well preserved on account of the care of the Calcutta Armenian Church Committee.

- During the period of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, a decree was issued which allowed Armenians to form a settlement in Saidabad, a suburb of Murshidabad, then the capital of Mughal suba (province) of Bengal. The imperial decree had also reduced the tax from 5% to 3.5% on two major items traded by them, namely piece goods and raw silk. The decree further stipulated that the estate of deceased Armenians would pass on to the Armenian community. By the middle of 18th century, Armenians had become very active merchant community of Bengal. In 1758, Armenians had built a Church of the virgin Mary in Saidabad’s Khan market.

Armenian Apostolic Church of St. John the Baptist

Within the Persian Empire, Armenians were deported in large numbers to New Julfa, on the outskirts of Isfahan, early in the seventeenth century. Many pushed on to India and Southeast Asia in the eighteenth century, as conditions turned against them. Found chiefly in Burma, the Malay peninsula (particularly Penang and Malacca), and Java, Armenians were usually accepted as 'European' or 'White'. They tended to emigrate further from around World War I, notably to Australia.

Armenians in Burma suffered over time from their close association with the independent Burmese rulers. Major Armenian traders were employed as officials, especially in charge of customs and relations with foreigners. They survived the First Burmese War in 1826, when the British annexed the fringe provinces of Arakan and Tenasserim. However, the British conquest of Lower Burma, the commercial heart of the country, in 1852, led to renewed accusations that Armenian merchants were anti-British, and even pro-Russian. Nevertheless, the Armenians of Yangon built their church in 1862, on land presented to them by the King of Burma.

The 1871-1872 Census of British India revealed that there were 1,250 Armenians, chiefly in Kolkata, Dhaka and Yangon. The 1881 Census stated the figure to be 1,308; 737 in Bengal and 466 in Burma. By 1891, the total figure was 1,295.

The Armenian Apostolic Church of St. John the Baptist still stands at No. 66, 40th Street (now Bo Aung Kyaw Street) in Yangon. According to its records, 76 Armenians were baptised in Burma between 1851-1915 (Yangon, Mandalay and Maymyo (now Pyin U Lwin)), 237 Armenians were married between 1855-1941 and over 300 Armenians died between 1811-1921.

Church of the Holy Resurrection

The last of the Armenians in Dhaka, Bangladesh

[September 01, 2008]

Dyuti Monishita follows the trail of Dhaka's Armenian Church and unravels the history of the community of Armenian traders who settled on the banks of the Buriganga before the rise of British India.

Michael Joseph Martin (Mikel Housep Martirossian) is possibly the last Armenian living in Dhaka. As the custodian of the Church of the Holy Resurrection and the cemetery within the church compound, popularly known as the Armenian Church, he has jealously guarded the church like a living sphinx.

He had been fighting off intruders and facing challenges for more than two decades now, the perfectly preserved condition of the Church building is his doing.

"People don't look back," says the eccentric toothless old man. "Times have changed," he sighs, "all they want are high-rise buildings and financial gain. People couldn't care less about the past and the marks left by it."

"Things were different back then", says the old and wrinkly Motaleb Ali, who has been living in Armanitola and have witnessed multitude of changes. "When we were young, the church was an open place. It was open to everyone, and I remember I would go there with my friends and sit in the cemetery and for hours and talk. But then, those were the times when you could sleep with your doors open at night, and there would be no intruders."

Armanitola, so named after the large Armenian community of traders who settled there in Mughal times, is symbolised by the Armenian Church which still stands proudly among all the weathering buildings and sickly sweet smelling chemical factories. The church bell stopped ringing a long time ago, though once, the chime of the bell was characteristic of the locality. Not much has changed within the walls of the Church, since its establishment in 1781. The cemetery still bears tombstones from the 18th century and the Church is still very serene inside.

"You see, there was no church before. There was only a small chapel for praying. But with growing congregations, it was not possible to accommodate so many people in the chapel," Michael explains, "that is why a church was built in 1781." The grounds inside the walls of the church are dotted with countless tombstones and epitaphs. The eccentrics are extended beyond Michael, the custodian. "I sleep on the graves at night, and not even a single mosquito bites me," the guard happily informs and points at his favourite grave to sleep on. The grave is allotted to one William Harney, a military veteran who was born in Belfast, Ireland in 1830 and died at the age of 71 in 1901 in Dhaka. The inscription on the tombstone reads, "It was hard to part with you grandpa. No eyes can see me weep. But ever in my aching heart your beautiful memory keep." The oldest grave is dated 1762, "there were older graves. But many of the gravestones were stolen during the 1971 war. So that's the oldest for the time being," Michael says.

Armenians were traders, who first came to Bengal following the footsteps of Persian adventurers, and in the course established their own trading community there, recognised as such by the Mughal government since late 17th century.

Armenians were mostly engaged in export trade paying a duty of 3.5 per cent to the government. The Nawabs are known to have engaged them to transact their personal businesses openly or clandestinely, and the European maritime companies engaged them as local representatives and their vakils (spokesperson) to the royal courts. Their economic and political influence was illustrious, with their dominance in jute and silk industries. Professor Sharifuddin Ahmed of history department, Dhaka University, says, "The Armenians excelled in trades such as textiles, jute, indigo, salt, zamindari, etc." However, the exact time of their arrival in Bengal is not known to this day. But a considerable number of Armenians arrived in the region during the Mughal period, in order to embark on profitable businesses.

Armenia is a landlocked mountainous country in Eurasia between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea in the Southern Caucasus. It borders Turkey to the west, Georgia to the north, Azerbaijan to the east, and Iran and the Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan to the south. A transcontinental country at the juncture of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, Armenia has had and continues to have extensive socio-political and cultural connections with Europe. Naturally, with its prime location, Armenia is full of history and has been closely linked with trading for time inestimable. Mohammed Rokibuddin, another local says, "I have heard from my grandfather that the Armenians had contributed a lot to our economy. I heard about their wealth and their lavish houses. The stories sounded like a fairy tale when I was little."

The most influential Armenians of that time were Pogoses, Agacy, Michael, Stephen, Joakim, Sarkies, Arathon (also spelled as Aratun), Coja (also spelled Khojah) and Manook (also spelled as Manuk) families.

According to a book called 'Smriti Bismritir Dhaka' in Bengali language, written by a very celebrated historian Muntasir Mamoon, Khwaja Hafizullah, a merchant prince, laid the foundations for the Dhaka Nawab Family by accumulating wealth by doing business with Greek and Armenian merchants. This trend was followed by his nephew and the first Nawab of the family Khwaja Alimullah. Parts of the gardens of Shahbag, Ruplal House, a major landmark in the old part of Dhaka, and the land where Bangabhaban stands belonged to Armenian zamindars. There is still a Manuk House inside Bangabhaban, bearing the name of the original owner's family. Although, Armanitola was where a lot of Armenians had settled, a number of them lived in the neighbourhood as well. The Armenians had built lavish homes around the city for comfortable living. Many of those structures still remain to this very day and hold their places as landmarks.

They also played a major role as patrons of education and urban development in Dhaka. The Pogose School, the first private school in the country, was founded by JG Nicholas Pogose, a merchant and a zamindar. P Arathon was the headmaster of the Normal School. According to the Dhaka Prakash, a newspaper of his time, students in his school scored better in examinations than students of other schools in Bengal, including the one in Hoogli, now in India's West Bengal state.

Being traders for hundreds of years, the Armenians had keen eyes for what business or trade would be lucrative, and that is why they were dominant in the jute and indigo industries. The noted jute traders included Abraham Pogose, M David, C Sarkies, M Catchhatoor, A Thomas, J G N Pogose and Michael Sarkies. Among them, the most distinguished was M David, he used to be called ?The Merchant Prince of East Bengal?. Horse carriages as a mode of transportation were introduced by C M Sarkies in 1856. At that time, the number of carriages was only 60, but by 1889 the number had increased to 600. This is how lucrative the business turned out to be. There were evidences of shops owned by G M Sarkies and C J Manook in different parts of old town. In fact, a very well known liquor store of that time was owned by an Armenian. ?During the British period, the Armenians maintained close contact with the British and they also had shops where they sold all sorts of European goods?, says Sharifuddin.

During the mid 1800s the number of Armenians in Dhaka started to migrate to West Bengal with the coming of British Raj. "Due to their close contact with the British, the Armenians started to act according to the activities of the British. Some went away to Britain and other European countries", Sharifuddin says. "The Armenians never saw themselves as a part of this country or culture. They have always distinguished themselves from people of this region. That is why they moved on with the rise and fall of the economy of Bengal", he concludes. And the population of the Armenian community had dropped to 121, and the economy had started wane as time went by and slowly the Armenians started to fade away until no one was left, and only the church stood in confirmation of their glorious existence.

As Michael paces among the tombstones and inspects the church, it is mournfully apparent that he is advancing in his years, and the future of the church which still stands strong, looks bleak. For Dhaka's sake, it will be a tragedy if the last Armenian takes with him the history of the Armenians who settled in Bengal.

Armenian Apostolic Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator Singapore

The HistoryThe Armenian Apostolic Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator is the first Christian church built in Singapore in 1835. Designed by Irish architect, George D. Coleman, it is considered as one of his masterpieces.

The HistoryThe Armenian Apostolic Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator is the first Christian church built in Singapore in 1835. Designed by Irish architect, George D. Coleman, it is considered as one of his masterpieces.

As the number of Armenian families was growing in the early 1830s due to business prospects in Southeast Asia, a place of worship was deemed necessary. In 1833, the land was acquired from the government of the time. Majority of the funds needed for construction was raised by Singapore Armenians, as well as, Armenians of Calcutta and Java.

On 26 March 1836, the church was consecrated and dedicated to St. Gregory the Illuminator, a patron saint and the first official head of the Armenian Apostolic Church. In 1973, the building was gazetted as a national monument by the National Preservation Board.

The year 2011 marks a special milestone in the Church's history. On 26 & 26 March 2011, over 160 Armenians (Archbishops, Government Officials, Dignitaries, friends) from 19 countries joined the local Armenian community in Singapore in celebrating the Church's 175th Anniversary. This spiritual place serves as a tribute to the once influential Armenian community of Singapore. They were lawyers, merchants, and entrepreneurs. Famous among them were the Sarkies Brothers who built and managed the Raffles Hotel, Agnes Joaquim who hybridised the orchid Vanda ‘Miss Joaquim’ (named as Singapore’s national flower), and Catchick Moses who co-founded the Strait Times.

The Church The interior of the church, namely the vaulted ceiling and cupola, is based on traditional Armenian Church architecture. The painting above the altar is of Christ and his Apostles at the Last Supper.

As for the exterior, a tall spire tops the building, while Doric columns, bordered by balustrades on both sides, sustain the white portico. The original design, a domed roof and bell turret (also another feature of the Armenian Church architecture), had to be altered because of safety reasons.

Writing on the occasion of the consecration in 1836, the newspaper THE FREE PRESS commented « …this small but elegant building does great credit to the public spirit and religious feeling of the Armenians of this Settlement ; for we believe that few instances could be shown where so small a community have contributed funds sufficient for the erection of a similar edifice…which is …one of the most ornate and best furnished pieces of architecture… ».

The Garden Within the tranquility of the tropical landscape lies the Memorial Garden with the tomb markings of Armenians who died in Singapore. The tombstones were transported here in the early 1970’s from the Bukit Timah Cemetery by an American-Armenian, Mr. Leon Palian, residing in Singapore at the time. The stones were assembled to form the Memorial Garden, a sanctuary to a small community with a strong heritage and ties to the socio-economic development of this country.

The Parsonage The parsonage house dates back to 1905 and was built for the living accommodations of the residing priest. Today, it serves as the administrative offices of the Armenian Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator. A group of dedicated volunteers manage all the administrative aspects of the Church - The Church operates without any overhead expenses and 100% of all donations are directed toward the maintenance and upkeep of the property.